Don't let DDOS silence your message

16 Nov 2022 - Justin Higgins

Over the last decade or so it has gotten easier and easier to setup a website, either by using one of the many hosted services available or running your own server. This is great for media diversity, and provides a publishing mechanism that is not beholden to any rules or content standards outside of the law. However, it also provides another way journalists and their organizations can be attacked, and their online voice silenced.

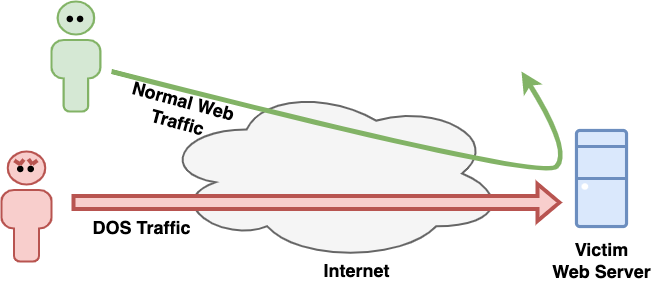

In particular, one of the easiest and most reliable ways to take a web site offline is to use a Denial-Of-Service (DOS) attack. This is when an attacker makes so many requests to a website that it either exhausts server resources or causes congestion on the network the web server is attached to, preventing anyone from accessing the site and making it appear offline.

This kind of attack can initially be very effective, but can usually be defeated by blocking the attacker with firewall rules or access control lists on a network device somewhere between the attacker and the victim's server.

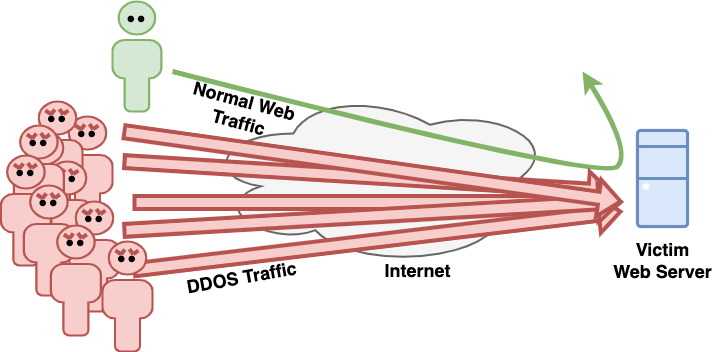

More effective, and these days more common, are Distributed-Denial-Of-Service (DDOS) attacks. These work much the same way, but instead of a single source of attacking traffic, the attacker uses a botnet or reflection attack to send traffic from hundreds or even thousands of sources.

This type of attack is much more difficult to defeat because there are too many source addresses to filter out with a firewall and the amount of traffic sent during an attack is often so large that it not only exhausts network resources on the web server, but floods the whole network that server is connected to. In extreme circumstances, upstream networks are overwhelmed too and sometimes an entire country's internet connection can be flooded, blocking all traffic inbound or outbound to the rest of the world.

The Rise of DDOS

The number of DDOS attacks has been steadily rising over the last decade. According to the Cisco Annual Internet Report, the number of attacks has risen from 7.9 million in 2018 to 13.9 million in 2022 with the largest attack reported by Cloudflare a whopping 2.5 Terabits per second in size (that's equivalent to sending the entire contents of Wikipedia five times a second!).

DDOS attacks are used against a wide range of organisations with journalists and their organizations especially well represented. During the war in Ukraine this year, the most common target for DDOS attackers in Ukraine were media and broadcast organizations.

These attacks and services are unequivocally illegal, but their low cost and plausible deniabilty ensures their popularity with the unscrupulous. Anyone can procure a DDOS attack from 'Booter' or 'IP Stresser' services. These services are often offered in public under guise of being a network testing tool and can sometimes be confused with legitimate security offerings. Prices are as low as $100US for attacks over 50 Gigabits per second and 3 hours in duration.

Is there a fix?

The good news is that the tools to protect against DDOS attacks have greatly improved alongside the rising number of DDOS attacks. Servers hosted in large cloud and hosting provider networks like AWS and Google are largely immune to DDOS attacks as those providers usually provide DDOS protection for free and they have enough network capacity to be able to absorb and defeat any attack. Likewise, content delivery networks like Akamai and Cloudflare are able to offer highly effective DDOS protection to customers outside large cloud networks by intercepting DDOS traffic before it gets to the victim's server. Cloudflare even offers it for free.

What about the rest of us?

Not everyone is able or willing to use large corporate cloud services and many popular web sites are run by news organisations themselves either in colocation data centres or straight out of the office. In these scenarios, it is much harder to protect against all DDOS attacks, but there are a few things you should do ahead of time to improve your site's resilience.

Talk to your Internet Service Provider (ISP) ahead of time

The standard response from ISPs when one of their clients DDOS'd is to reconfigure their network to drop or 'blackhole' all traffic going to that customer server. The DDOS traffic is likely to impact some of or all of their other customers, so it's understandable they would take one customer offline to save the others. If you speak to your ISP ahead of time, you can find out exactly what they do in that situation and whether there's anything that might keep your site online during a DDOS. Your ISP will also appreciate any information you have about when or who you might be attacked by.

Some questions to ask your provider are:

- What do you do if one of your customers gets DDOS'd?

- Does your network have any DDOS mitigation capability?

- What do you do if your network infrastructure comes under attack?

- What network capacity do you have available to absorb inbound DDOS traffic?

- Is there anything you would like us to do if we detect a DDOS attack against our server?

This will allow you to better gauge your risk of DDOS and arrange a plan of what to do if a DDOS attack happens. The plan should include 24/7 technical contacts for both parties, how notification and updates will occur and any technical actions either side will take.

Have a redundant site with a failover mechanism

If your website is an important part of your organisation's mission then it's a good idea to have a redundant web server at another physical site regardless of DDOS attacks. In the event of a DDOS attack, it's often possible to get your site back online by changing your DNS to the redundant site. The DDOS attackers might see the DNS update and change their DDOS to attack the secondary site too, but often the attack is performed by a third party and will not respond to DNS changes, allowing you to defeat the attack with a simple DNS change.

Deploying a redundant site will also give you other options, you could:

- Host the redundant site on a very small and low cost virtual server in a cloud provider and scale it up on-demand when a DDOS occurs

- Place the redundant site behind a Content Delivery Network (CDN) that provides DDOS mitigation, so you only pay for the CDN services during a DDOS attack

- Offer a simplified version of your site consisting of only static content that can be served cheaply from a high volume hosting service that includes DDOS mitigation

Many failover mechanisms are available, but simple DNS failover usually works well for a DDOS attack. In any case, you should make sure your DNS servers are not hosted on the same network as your web server as that would prevent you from propagating a DNS change during a DDOS attack.

Whatever failover setup your choose, be sure to test it regularly so you know that it works and everyone understands what will happen during a failover event and how their workflows will be impacted.

Harden the edge of your network

If your site does get attacked, and you're running the network that your web server is attached to, often one of the things to fail first is the border router or firewall you have that connects your network to the Internet. This is because the composition of DDOS traffic is often wildly different to normal internet traffic and is made up of a much higher rate of smaller network packets. So even if your firewall has plenty of day-to-day capacity, it will immediately fail when the DDOS traffic arrives, stopping your entire network from accessing the internet.

</div>

To prevent this, use a router or firewall that is capable of handling the maximum number of packets your internet connection can sustain (AKA 'line speed'). This usually means a device with special purpose hardware built to handle traffic at line speed. Examples of this are higher end Cisco ASA firewalls and Juniper MX routers. Though there are a lot of other options out there. The metric you should look for on device datasheets is "maximum packets per second" or "maximum 3 way TCP connections per second".

You should also configure the firewall to allow only the required traffic to your web server (TCP port 80 and 443 inbound) as this will protect the web server from some types of DDOS attack that send UDP or non-web traffic to their targets.

Arms Race

One of the frustrating things about DDOS attacks is that the only way to guarantee that they can be defeated is by having more bandwidth available than the attackers. Since DDOS attacks are already so large, this means that the largest attacks can only really be defeated by backbone internet companies or international cloud providers. You should take that into account when determining how vulnerable your organization is to DDOS attacks, but for non-cloud deployments, being prepared before the first DDOS happens will help prevent your message suppression through cyber attack.